Owen Hu, Grade 12

In 1973, Phyllis Webstad wore a bright orange shirt on her first day at St. Joseph Mission Residential School. That same day, her belongings and identity were taken away—and she never saw her orange shirt again.

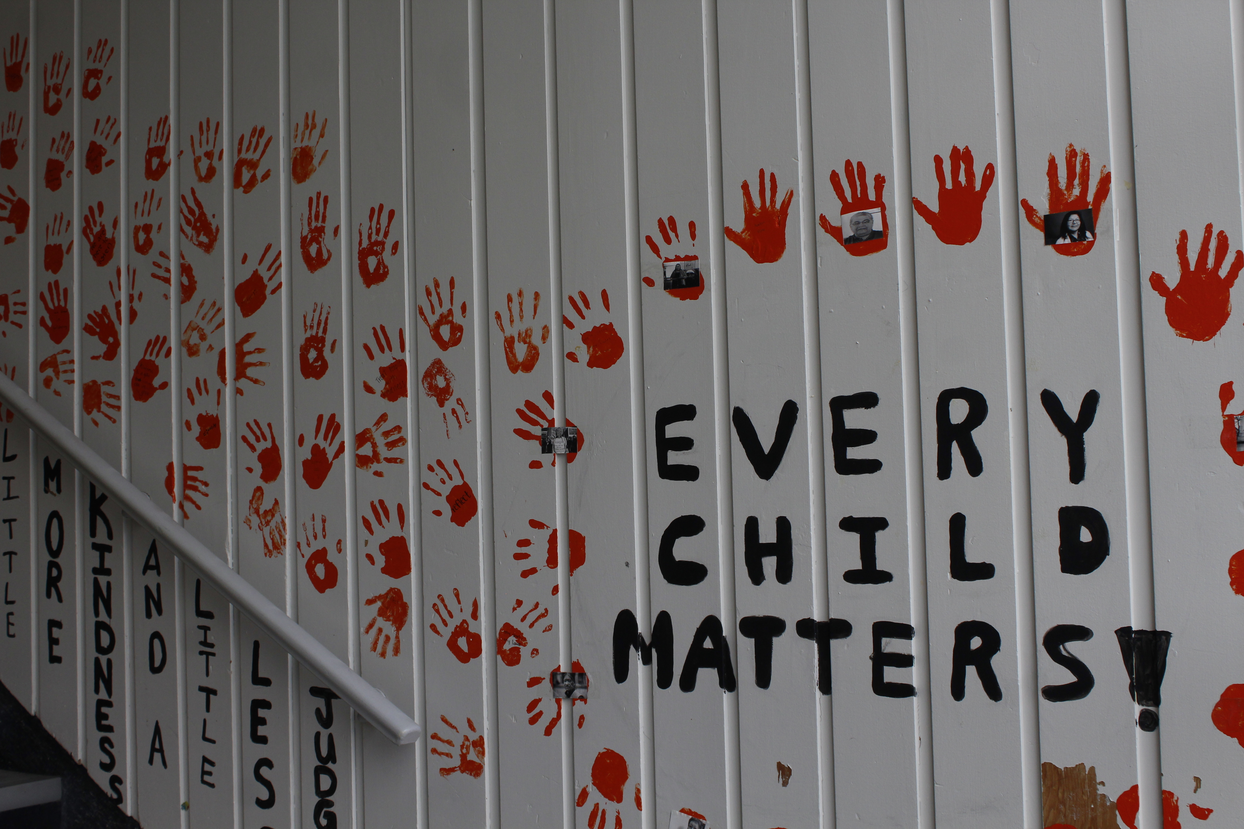

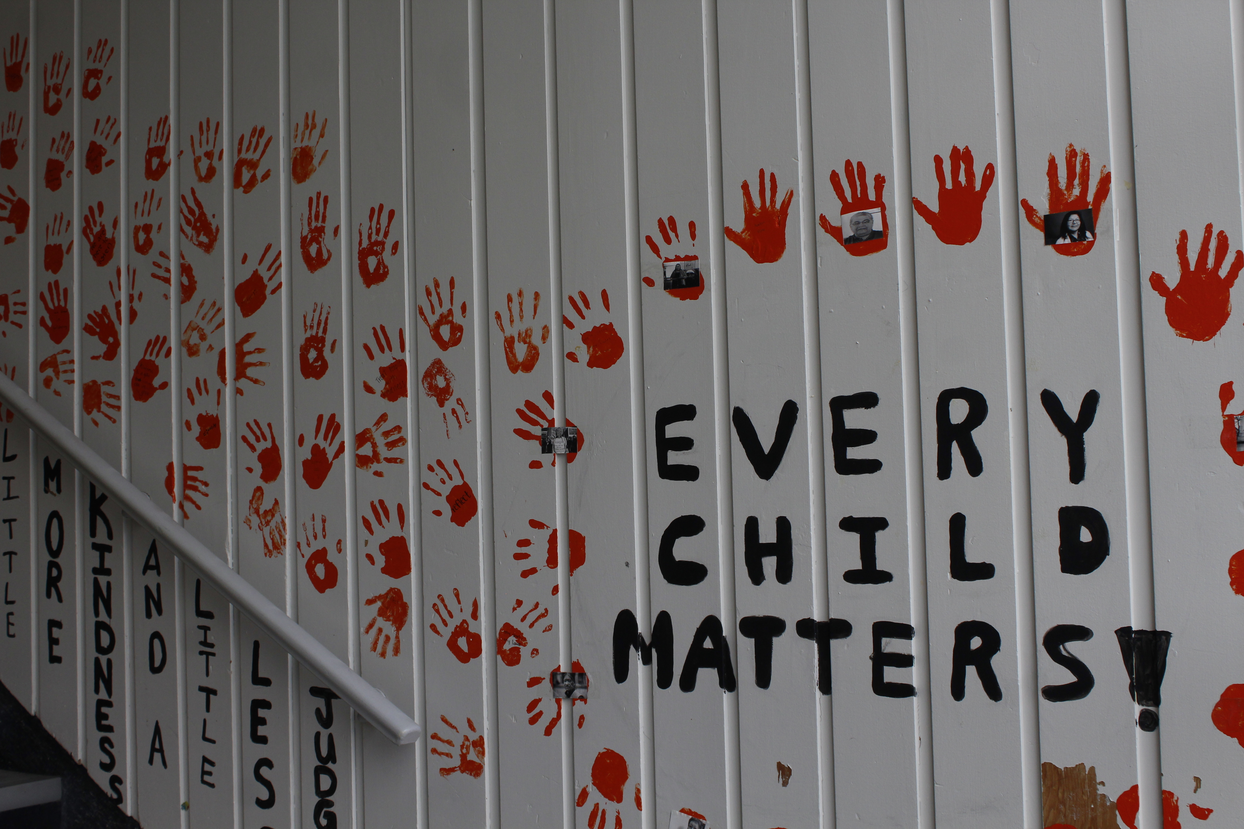

Today, Canada commemorates Orange Shirt Day around the time Indigenous children were historically taken from their homes to honour the victims of residential schools’ heartbreaking legacies. The Burnaby North community, too, embraced Indigenous culture and history that day.

As a member of Yearbook, I was very fortunate to have taken part in a traditional ceremony led by North’s Indigenous Leadership class. Along with two photographers, we were there to document the lasting impact of residential schools and Indigenous communities’ resilience today on the path to reconciliation.

Sitting in a circle out in the courtyard, the group passed around an eagle feather, and we all introduced ourselves. Four orange shirts lay in the centre, symbols of solidarity for the thousands of Indigenous children lost to Canada’s residential schools. Our ceremony leader began with a time of reflection. The group dialogue was difficult but necessary, the air heavy and overcast. I recall having my eyes closed during the moment of silence, only to reopen them as I sensed the smoky smells of burning herbs during the smudging ceremony; aromas of burning sage, juniper, and lavender soon waft up, and I embrace the fumes as their upward flights end on my face, my arms, and my legs. This smudging is the traditional ceremony involving burning herbs—ones that residential schools strictly prohibited—to cleanse ourselves of negative thoughts.

The Coast Salish Anthem was then sung to a slow drum beat, a powerful demonstration of cultural resistance against Canada’s history of oppression.

“Today’s a heavy day, and we want to keep our hearts open.”

A heavy atmosphere permeated the discussions of injustice, but I also sensed a feeling of positivity—a feeling that things will change, a feeling of hope. Being in that circle, one from which society tells me I’m to be separated from, was powerful; it’s a feeling I can’t quite describe other than knowing I was fully welcomed into the community. Even though it was a temporary embrace to document an important part of Burnaby North’s culture, the circle further immersed me into Canada’s complicated and painful history, of which I was previously unaware.

From the smudging to the drumming, the positive energy to the embrace: I truly am lucky to have taken part in an experience that helps me understand how lived experiences transcend cultural—and constructed—boundaries.